When South Carolina architect Louis Wolff built his dream house in 1962, he designed it following modern architectural principles of form, line and function. Yet he insisted that the house was contemporary, not modern, softening what he considered stark elements of strict modernism to make a comfortable fit for his family. Wolff was not afraid to stretch the boundaries of other people’s definitions—either in architecture or in life.

When South Carolina architect Louis Wolff built his dream house in 1962, he designed it following modern architectural principles of form, line and function. Yet he insisted that the house was contemporary, not modern, softening what he considered stark elements of strict modernism to make a comfortable fit for his family. Wolff was not afraid to stretch the boundaries of other people’s definitions—either in architecture or in life.

The only son of the only Jewish family in tiny Allendale, South Carolina (the town where artist Jasper Johns spent his childhood), Louis left the family store behind to study architecture at Clemson, then a military college, graduating in 1931. He later worked his way through the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture playing trumpet in a dance band, earning his Master’s certificate. As a commissioned officer he served in the Army Corps of Engineers during World War II and was promoted to the rank of Colonel at war’s end.

In 1948, Wolff joined fellow Clemson graduates to form Lyles, Bissett, Carlisle & Wolff, Architects and Engineers. LBC&W, as it came to be known, was the most prominent architectural firm ever to come out of the Southeast. In its heyday of the late 1950s through the mid-1970s, LBC&W expanded its headquarters in Columbia and opened satellite offices up the eastern seaboard. The firm specialized in designing government, university and commercial buildings with a company aesthetic of corporate modernism, the preferred international style of commercial buildings post-WWII. The firm won excellence in design awards from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and other associations; its successful business model was taught at Clemson architectural school. According to an article in the former Sandlapper magazine, as of mid-1974 LBC&W had completed “some 2,000 projects, costing about $2 billion, a significant contribution to its community, state and nation.”1 Signature buildings still in use today include the main U.S. Post Office and the University of South Carolina Undergraduate Library in Columbia, the Clemson University Library, and the U.S. Tax Court building in Washington, DC.

LBC&W partners each served as South Carolina AIA president and all four were named AIA Fellows; at the time of his award, Wolff was only the seventh South Carolinian architect to achieve FAIA status. Attuned to his roots, Wolff actively participated in Clemson and Penn alumni associations, helping raise funds for architectural scholarships. He remained an involved presence in the Columbia Jewish community throughout his lifetime.

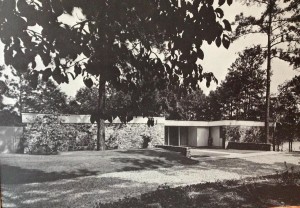

Wolff spent much of 1962 supervising the construction of his Columbia, SC, home. The house, on a 1.2 acre wooded, lakeside property, is horizontal to and set back from the road, effectively maximizing both privacy and views. Half of the nearly 6000 square-feet house is built into a hill, creating both one-and two-storied living spaces. The main exterior material on the façade is Pennsylvania fieldstone; the two sides of the house that face the lake are constructed primarily of glass, allowing continuous daylight and affording unobstructed lake views. Wolff followed Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophy of organic architecture, harmoniously integrating the design with its natural surroundings. The residence was highlighted in a book of architecture celebrating South Carolina”s bicentennial, which noted its effective relationship to the property on which it was built (see photo).

Louis Wolff died suddenly in 1977. The U.S. was still reeling from the economic effects of a recession that included a construction bust, and LBC&W was dissolved around that time. But the firm left behind a legacy of design and a generation of architects and engineers who continued to produce work at other firms and mentor the next generation.

Wolff”s widow, Elsie, passed away in January 2013 and the family residence is on the market for the first time this autumn. Visitors to the house will notice how “now” the space feels, with its main level open concept and room-to-room flow, high ceilings and floor-to-ceiling windows in common living spaces, skylights in interior hallways, and the use of sleek, walnut cabinetry and floating shelves throughout the house. Furniture designed by Wolff currently remains in the home, along with original Knoll and Herman Miller pieces from the era and period art, creating an impression of mid-century meets modern revival.

With interest in mid-century modern homes surging over the last decade, even Wolff would have found it hard to imagine how very contemporary his house, 50 years later, still feels.

THE END

1 “LBC&W: from the Attic to the High-Rise and Beyond,” by Lynn A. Gordon, Sandlapper. The Magazine of South Carolina, July 1974.

UPDATE 9/30/2015 – The house sold in spring 2014 to an individual committed to preserving its architectural integrity, and has been submitted for consideration on the National Historic Register of Homes. Curricula on LBC&W are taught in classes at Clemson University architecture school and the University of South Carolina art history and preservation.